Sometimes, the underdog wins, if only for a brief, shining moment.

That was the situation at American Motors at the dawn of the tumultuous 1960s.

The years 1958 to 1961 don’t take up much space in history books (unless you’re focusing on the Space Race), as there existed relatively little conflict in a world now used to global battles. The Baby Boom was in full swing, the Camelot years of the JFK presidency was poised to begin, and hippies, women’s lib, and the incendiary final years of the civil rights struggle were still years away.

Only the pesky matter of The Bomb kept people up at night, though a solution (Diazepam, aka Valium) was imminent.

In the auto industry, however, things weren’t so Leave It To Beaver placid. Competition was fierce between the Big Three automakers, and by the late ’50s the smaller companies had either thrown in the towel or were struggling to stay afloat.

After a merger with Studebaker, Packard’s last year was 1958 (and what a grotesque thing it had become by then). Studebaker brainstormed to find a way to overcome the massive financial hit it took following the merger a few years earlier, and managed to pull off a modest recovery that lasted until the mid-60s.

Nash and Hudson, whose best years were marked in the ’30s and ’40s, ceased to exist after 1957, the result of a mighty 1954 merger between Nash-Kelvinator and Hudson Motor Car Company – at the time, the largest in history. That merger saw the birth of a new automotive entity – American Motors Corporation (AMC).

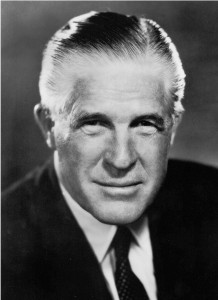

Leading the new company was president and CEO George W. Romney, a former VP at Nash-Kelvinator who took on the top role after the death of George W. Mason a few months after the merger. Romney (father of 2012 Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney) had the old makes soldier on in an increasingly competitive marketplace while planning a new strategy for success (or at least survival).

Official portrait of George W. Romney, taken while he was U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. (Public domain image)

Luckily for the company, Romney had brought binders full of ideas to his new role, and quickly decided that in order to compete with the Big Three, AMC had to offer something the big guys weren’t. That meant compacts.

Romney viewed the competition’s offerings as “gas-guzzling dinosaurs”, ripe for slaying, and set out to do just that.

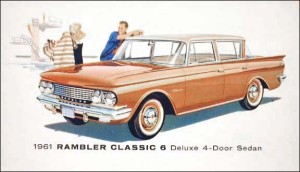

With the remaining Nash and Hudson models killed off at the end of 1957, AMC poised its new lineup for a 1958 debut, led by the compact Rambler brand – a make AMC had poured all of its efforts into.

Engine size, vehicle size, tailfin height and sticker prices were all reaching for the stars in the late ’50s, but luck was in AMC’s corner.

As 1958 dawned on the gaudiest, most excessive and expensive vehicles Americans had ever seen (especially those offered by Buick, Cadillac and Lincoln), a sudden, sharp recession – by far the worst of the post-war boom – hit the United States. Consumer prices rose across the board and vehicle sales dropped 31% industry-wide.

The only American car company to turn a profit that year? American Motors.

Helped by favourable reviews that emphasized the Rambler’s price and fuel economy, as well as a widespread television and product placement marketing campaign (which included Disney!) orchestrated by Romney himself, Rambler – and AMC – was off to a roaring start.

With the success of the Rambler American and Rambler Classic line of vehicles, the traditional big players in the industry soon took notice and immediately began designing their own small cars, which were introduced in the early ’60s.

In 1960 and 1961, Rambler ranked third in domestic auto sales, with the latter year seeing the company enter into the industry’s first profit-sharing plan for its United Auto Workers-represented employees. Innovations followed that were later picked up by the Big Three, including standard reclining front bucket seats, optional front disc brakes, and the ‘PRND21’ automatic transmission sequence.

Research work was even done in support of a fully-electric car powered by a self-charging battery, though that effort clearly went nowhere.

The company took a shift away from the ‘think small’ strategy in 1962, after Romney resigned in order to run (successfully) for Governor of Michigan, where he grew the civil service and imposed the first income tax in the state’s history. Later, he went on to serve as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Nixon, where his ideas – including ambitious social housing and de-segregation proposals – fell mostly on deaf ears.

For an interesting look at Romney’s policies (contrasted with those of his son), enjoy this somewhat long article in a liberal-perspective magazine:

http://prospect.org/article/cost-living-apart

(Romney was also a strong civil rights supporter who expanded state social programs and championed anti-discrimination laws. For more on that… http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/08/how-george-romney-championed-civil-rights-and-challenged-his-church/261073/)

Trouble at the ranch

Anyhoo, back at the AMC camp, Romney’s departure meant there was a new captain at the helm – Roy Abernathy – who shifted the company towards a more diverse lineup. This meant a newfound focus on large cars, with the thinking that people weaned on Rambler’s compacts would one day want to move up to something bigger.

This strategy didn’t pan out and Rambler floundered in the marketplace, with overall sales slashed in half by 1967. Bleeding money at an alarming rate, AMC’s end looked near until new CEO Roy D. Chapin, Jr. arrived with famed designer Dick Teague in tow.

Chapin brought on a new executive, cut costs where possible, and made the compact Rambler American the company’s short-term focus, chopping down the sticker price to lure in buyers. In the background, Teague and his fellow designers worked to create new, youth-oriented vehicles from existing parts and vehicle stampings.

Once again, all of this work was backed up by aggressive advertising.

The intermediate-sized Rambler Classic, introduced on an existing chassis in 1961, was renamed the Rambler Rebel in 1967, before the Rambler name was dropped in favour of AMC badging in 1968.

The Classic had long been the bread and butter of the Rambler lineup, first offered with a 195 cubic inch straight-six or 250 cubic inch V-8. Covering three trim levels and multiple body styles, the Classic’s engine choice was fleshed out to three sixes and two larger V-8s as the ’60s progressed.

The renaming of both Rambler and the Classic had the goal of shaking up the brand’s image and moving buyer’s minds away from negative connotations of the recent past.

Under the new strategy, AMC entered the 1970s in good shape and with lots of buzz, purchasing Jeep’s vehicle operation in 1970 before things started to get really weird (Pacer, Gremlin, Matador coupe) in the mid-to-late ’70s. Obviously, at some point the company’s water supply had become tainted with hallucinogens.

After introducing the renowned and innovative AMC Eagle 4-wheel-drive wagon in 1979, the company entered into an ill-fated partnership with Renault in 1980, and immediately began a fast slide into oblivion. Renault left the American market in 1987, dropping its majority stake in AMC, at which point Chrysler Corporation purchased those remaining shares.

The formerly AMC-owned Jeep was folded into the Chrysler stable, while Renault-designed AMC products that had been in the works were marketed under a new brand, Eagle, starting in 1988. Eagle soon became just another make selling badge-engineered Chrysler products, like Plymouth and Dodge, though with some sporting pretentions in the form of the Talon coupe.

Eagle was unceremoniously dropped in 1999.

And so ended the rocky, confusing lineage of American Motors – the quirky car company that was once part of a refrigerator company and was once run by Mitt Romney’s unusually progressive yet devoutly Mormon/Republican dad.

If this tale has taught us anything, it’s to not go all-in on identity politics, and to be very wary of mergers.