1979 or 1980 R-body Chrysler New Yorker, spotted in Gatineau, Quebec.

1979 was a turbulent year in America.

Gasoline had suddenly became expensive again thanks to the Iranian Revolution, interest rates were rising like mercury in a noonday Texas thermometer (as was inflation), and disco seemed poised to take over the world…and our kids.

On the automotive front, the Big Three automakers were struggling against economic pressures and the sudden appearance of a new competition – fuel-efficient Japanese compacts that tempted buyers with savings at the pump and low starting prices.

Nowhere in Detroit was the financial pressure greater than in the headquarters of Chrysler Corporation, which was desperately trying to avoid bankruptcy following a decade of non-stop punches that shook the industry to its core.

In addition to trying to secure bailout money from the federal government (while wooing eventual savior Lee Iacocca into their top-floor office), Chrysler was trying to compete against new, downsized models from GM (1977) and Ford (1979). And, given its dire situation, it had to create something competitive using little money and mostly off-the shelf parts.

As a rule, the downsized full-sizers introduced in the late-70s needed to appear fresh and new, have as much interior room (or more) than their land-barge predecessors, weight less, while consuming less precious, endangered gasoline.

For Chrysler, that meant the creation of the ‘new’ 1979 R-body line of vehicles – the Chrysler New Yorker and Newport, Dodge St. Regis, and (eventually) Plymouth Fury. The R-bodies have long fascinated me, as they really represent the end of the traditional full-size lineage of Chrysler vehicles – a slapped-together vehicle created in desperation to bridge the gap between the excessive 1970s and the lean, modern 1980s.

As a result of the rapidly changing era – one advanced by Chrysler itself following Iacocca’s appearance – the R-bodies (produced from 1979 to 1981) quickly became rolling dinosaurs, and faded from both roadways and the public consciousness in a hurry.

A ’62 dressed up as a ’79

The word ‘new’ appears here with quotation marks because the R-platform wasn’t new at all. Rather, Chrysler had simply taken the old B-platform that underpinned the previous Dodge Monaco and Plymouth Fury (and dated from 1962), and created a new, yet traditionally-styled body atop it, while doing everything possible to shed weight.

The old, big-block 400 and 440-cubic inch engines were put out to pasture, replaced by the venerable 225-cid Slant-Six, as well as the trustworthy 318 and 360-cid V-8s. So extreme was the need for weight loss, Chrysler fielded the ‘new’ line of sedans with stamped aluminum, chrome-plated bumpers, aluminum radiators and brake cylinders with plastic components. The weight loss, totalling several hundred pounds, helped the car’s lineup of aging engines (strangled of horsepower by government-mandated emission controls) haul the lengthy sedans around town.

Once on the market, the R-bodies represented the most traditional of the Big Three’s big sedans. Big on the outside as well as the inside, the Chrysler stablemates could be had with all the baroque trappings a late-70s driver could desire – vinyl top, pillowed velour interior in gaudy colours, and the classic fake wire wheel hupcap/whitewall tire combination. The New Yorker, which was available in top-shelf ‘Fifth Avenue’ trim, continued the hidden-headlamp motif popularized by its predecessors, as well as offerings from Lincoln.

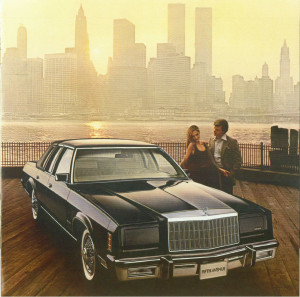

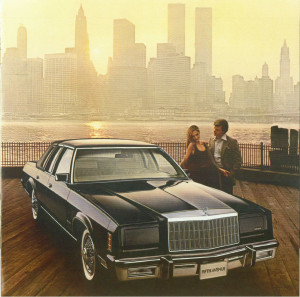

“Do you park your 1979 Chrysler New Yorker here often?” (Chrysler promotional photo)

Sales of the R-body ‘pillared hardtops’ (ie – no window frames) started off brisk, helped by commercials that searched high and low for fiscal bright spots in an R-body purchase, but soon tanked once the effects of the Iranian Revolution began to impact people’s wallets. 1980 saw an exponential decrease in units sold, and the same for 1981.

Police fleets snapped up the Newport, Fury and St. Regis in fairly large numbers, given their imposing size and sturdy platform, but none were ever regarded as performers. Most pursuit vehicles were bought with a decent 195-horsepower 360 under the hood (for 1979), mated to the ubiquitous and bulletproof 3-speed Torqueflight automatic transmission, though California fleets made do with less (190 horsepower), and Canadian fleets with more (200 hp), thanks to better exhaust systems and boosted engine compression.

In 1980, California’s air pollution regulations mandated that all police R-Bodies come equipped with a 165-horsepower 318, which caused “a monumental firefight” between Dodge and the officers and management of the California Highway Patrol, who complained of embarrassment when the car performed dismally in real-life applications.*

(Apparently, one of the requirements of a police vehicle is the ability to catch fleeing suspects)

By 1981, the jig was up for the R-body. Sales of the big Chryslers were circling the bowl, and the company had already bled so much cash that CEO Iacocca was forced (starting in ’79) to slash all unnecessary overhead in a bid to save the company. Iacocca’s ‘triage’ approach meant that the company’s attention was primarily focused on keeping costs down while it produced and aggressively marketed a revenue-generating vehicle tailored for the economic climate America found itself in.

That vehicular saviour was the K-car line of compact, front-wheel drive vehicles that first appeared as Dodges and Plymouths in 1981 and branched out to the Chrysler brand in 1982. After ’81, with the R-body gone, Chrysler’s full-size spot was filled by the (formerly) intermediate-sized M-body Chrysler New Yorker, Plymouth Gran Fury, and Dodge Diplomat.

The real, honest-to-goodness full-size Chrysler was dead.

Adios, big guy…

Today, 33 years after the last R-bodies rolled unceremoniously off Chrysler’s embattled Detroit assembly line, seeing one in the flesh is a rare occurrence. The 1979 or 1980 New Yorker pictured at the top of the post was such an uncommon sight, it needed to be documented. These cars do look better in black, though this example is suffering from sagging lower body trim, missing front bumper guards, and an absent wheel cover.

However, under the hood there likely lies a 318 that can be nursed back to life without too much trouble, if it isn’t already serviceable.

Hopefully, the owner of the New Yorker will ensure this relic of a largely-ignored chapter in American automotive history stays alive, and on the road.

1979 Chrysler Newport, the less-flashy brother of the New Yorker. (Image: Bull-Doser, Wikimedia Commons)

*(http://www.allpar.com/cars/dodge/R-bodies.html)