Driving the Trans-Labrador Highway in 2009 in the Grand Am ‘1.0’

Ottawa to Wabush, Labrador (2009)

I give full credit to lengthy childhood road trips for giving me the patience and imagination needed to perform epic solo road journeys later in life.

There were no headrest DVD players or iPads in those primitive days – the world outside my side window was my only entertainment as the countryside rolled past at 60 miles per hour.

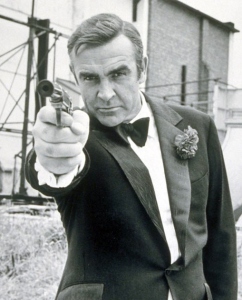

The inspiration for my journey.

Winging to the downtown of various cities is nice, but you don’t get a sense of the enormity of Canada by skipping the vast swaths of land in between. If you want to be a latter-day explorer, the car is your friend.

Five years ago, during a tumultuous time in my life (cue violins), I decided to cleanse my psyche and challenge myself a bit by throwing off the chains of civilization and driving into the unknown. It was just like Into the Wild, except that I survived and was back in four days.

My destination was Wabush, Labrador – a small mining town in the western part of the mainland area of the province. High in the taiga of Canada’s subarctic, the area harbours the world’s largest iron ore deposit and didn’t even exist on a map before the 1950s.

I had never heard of the place before then, but I had unknowingly read about it. Many people have, in fact – especially if they’re fans of 20th Century science-fiction.

The 1955 novel The Chrysalids by British author John Wyndham (Day of the Triffids, Village of the Damned) is a post-apocalyptic story set in the far future. A tale of a young boy growing up in an ultra-fundamentalist farming community in a now-temperate Labrador, the novel uses real geography to frame the tense, restricted world of 10-year-old David Strorm.

Wabush, Labrador – a remote iron mining town and the setting of the famous 1955 sci-fi novel ‘The Chrysalids’.

The village of Waknuk, where the novel’s characters obsess over maintaining a strict genetic purity out of fear of divine punishment, is really Wabush, Labrador. Other locations in Newfoundland and Labrador (with names changed slightly) make up the rest of the known world for the fearful inhabitants of the village.

The areas further from Waknuk and other such outposts are designated as “Badlands”, an endless area filled with genetic “Blasphemies” and “Deviants,” where humans fear to tread.

Thousands of years earlier, before God sent “Tribulation” to the land, Waknuk’s elders tell of great cities of light that buzzed with horseless contraptions and other unthinkable inventions – cities filled with people who fumbled with a newly-conceived type of bomb.

Having read the book not too recently, and wanting a road trip to a very unlikely location that would test my will, this became my goal.

Getting to Wabush from Ottawa is straightforward. Travel along the north shore of the St. Lawrence past Montreal, Quebec City and the Saguenay until you reach Baie-Comeau, Quebec. North from there runs a highway – Quebec Route 389 – better known as the Trans-Labrador Highway.

Since 2009, the Trans-Labrador Highway has seen nearly half a billion dollars in upgrades.

The only road link between Labrador and the rest of Canada, Route 389 runs 570km north from Baie-Comeau before it hits the border. Along the way, which is more unpaved than paved, there is a single town (about 8km from the border).

Newfoundland and Labrador Highway 500 takes over on the other side of the border, accessing Churchill Falls, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, and, since a few years ago, the southern coast of Labrador (Cartwright, Red Bay) and the ferry to St. Barbe, Newfoundland.

Wabush, a few kilometres from the larger Labrador City, is accessed via a spur highway that connects to highway 500. In 2006 I crossed the Quebec-Labrador border at Blanc-Sablon by way of Newfoundland, but Route 389 still remains the only mainland road link to Canada’s mainland highway network.

(Who can say they drove to Labrador twice for no particular reason? This guy!)

Into the unknown

At the time of the Wabush trek, I was driving a 2003 Pontiac Grand Am 4-cylinder with a 5-speed manual. A minimum amount of research showed me I’d be leaving civilization behind on the northern leg of the trip, and that basic preparations were needed.

A short walk to salvation! Emergency services on Quebec Route 389, aka the Trans-Labrador Highway.

Imagine driving the distance from Mississauga to Montreal on a narrow, winding, mountainous gravel road with no cellular reception, radio reception, intersections, streetlights, houses or towns. That’s what I was facing.

I later learned you can rent a satellite phone at the major points along the Trans-Labrador, and drop it off at any place that rents them. Other than that, the only emergency services were SOS call boxes placed every 50km along the highway.

Car quit on you? Help is only a 25km walk away! Mind the wolves.

It helps to have something of a fatalist approach on trips like these, because you’ll never be able to cover all the bases when it comes to your car’s reliability. Extra water, oil and especially a full-size spare (along with donut spare) are essential, but if your car decides it’s time to bite the dust, that’s it. You’re at the mercy of those unthinking, moving parts.

Best to just put those nagging worries at the back of your mind and watch the scenery unfold through the windshield.

Sharp turns and a bad road surface makes encountering other traffic on Route 389 an adventure!

Now, back to the trip. Bypassing Montreal by way of Autoroute 640, the trip to Quebec City via the 40 is a pretty dull 4-lane affair. Wanting to get to Baie-Comeau by dark (it was August, and the days were starting to get shorter) I blasted through Quebec City via the 440, leaving modern highways in my rear-view at Beauport.

Route 138 – the North Shore highway – is a scenic, narrow 2-lane road that hugs the shore of the rapidly-widening St. Lawrence, winding around quaint coves and along high bluffs.

Two hours northeast of Quebec City lies the Saguenay River, which is actually a sea-level fjord capable of accepting oceangoing cruise ships.

A short ferry ride across the Saguenay gives motorists a chance to stretch their legs before picking up the 138 again on the other side.

Hydro-Quebec’s Manic-5 hydroelectric dam (212 km north of Baie-Comeau) holds back the massive Manicouagan Reservoir.

Population and vegetation becomes much more sparse east of the Saguenay. Only one major town – Forestville – lies between that point and Baie-Comeau, which is itself 415km from Quebec City. Fewer villages, road signs and stunted trees set the stage for the next day’s journey into nowhere.

Baie-Comeau is one of those places that exists for some unknown reason. Unlike the only two places of consequence further up the coast – Port Cartier and Sept-Iles – Baie-Comeau doesn’t have a major railroad or seaport to justify its existence. Famous for being the birthplace of Brian Mulroney, the town of 22,000 has an infuriating road system that makes unfamiliar motorists drive parallel or away from the places they want to be.

GPS would have made short work of this problem, but it was 2009, remember. Dinosaurs still roamed the earth.

The next day dawned gloomy, windy and rainy, which was just perfect for a gravel road trip to Labrador. Like a responsible person, I brought along no food. Well, there might have been a bottle of pop or two (I tend to eat very little on road trips).

A narrow 2-lane forced road with aging pavement greeted me for the first 200-or-so kilometres of the trip. Being used to driving anywhere in Quebec, this was nothing new or shocking. Near the beginning of the highway, a roadside sign warned of the need to turn around and fill up if you didn’t think your tank would last you to the next service station, 211km away.

Iron oxide turns a lake blood-red near the Mont Wright iron mine, just west of Fermont, Quebec.

The only tourist site along the road appears 214km north of Baie-Comeau, and serves as the division between paved and unpaved road (or, at least it did in 2009). The Daniel-Johnson Dam, also known as ‘Manic-5’, is a hydroelectric generating facility featuring 14 buttresses and 13 arches – the largest of its type in the world.

Built from 2.2 million cubic metres of concrete, the 702 foot tall, 4,311 foot long dam holds back the 139.8 cubic kilometres of water contained within the Manicouagan Reservoir – itself an old asteroid impact crater.

Leaving the dam and its steady traffic of white, Hydro-Quebec Silverado crew cabs behind, Route 389 gave way to gravel and hard-packed dirt, the latter of which had the strength of dried mud. Near the edges of the road, soft sand would pull at your tires if you took a turn a little too wide. Another sign, too – this one reading ‘249km till next gas station’.

Crossing a gulf of nothingness usually leads to greater-than-posted speeds, and my car was no exception. After a few hours on that twisty course, my rally credentials were already half formed. I tried to maintain an average of 80 km/h to get the journey down to 8 hours or so.

In one picture, the Trans-Labrador Highway, the iron mines at Mont Wright, Quebec, and the Cartier Railway line, which connects to a distant St. Lawrence seaport.

There’s a saying by those who use the road that states in some places, you’ll be able to see your own taillights.

This isn’t far off. The Labrador and North Shore Railway, a rail line that originates in Sept-Iles and terminates in Schefferville, Quebec (northwest of Labrador City), intersects with the road multiple times over the space of a kilometre or so.

Up there, you don’t have flashing lights and a gate to warn of heavily-laden iron ore trains.

I’m told the Quebec government made significant upgrades to the road after 2009, so I can’t vouch for its current alignment.

The terrain along the route is typical of northern Quebec and Labrador – low to moderate rocky hills, small lakes and shallow, fast-flowing streams.

‘Lambkill’, a beautiful and deadly poisonous flower that grows across the north and in alpine regions.

Forested hillsides give way to peat bogs ringed by miniscule tamaracks and black spruce, while the ground is covered in white, spongy caribou moss.

In places, pink Sheep Laurel flowers (aka Lambkill) and white Labrador tea blossoms added much needed colour to a brown-grey-and-green landscape.

The flowers were nice, but my eyes were kept on the road, mainly to save my backside. A lack of alternatives means Route 389 handles lots of trucks lugging wide-load machinery – even whole houses – on their heaving, flatbed backs. Going into a blind corner carrying too much speed will spell the end of any over-enthusiastic motorist.

And don’t expect an ambulance to show up.

Modern civilizations 101

After the thrill of filling up at one of Canada’s loneliest gas stations (about two-thirds of the way up the road), an outpost that featured rentable cabins for overnight stays, I eagerly awaited reaching a town, a village, anything.

Being removed from civilization for the better part of a cold, dreary day makes you appreciative of things like traffic lights, electricity and the prospect of a hot meal and warm bed. The bed would have to wait, but it was with giddy excitement that I made my first turn after 562km of driving – a right turn, into Fermont, Quebec.

Between Baie-Comeau and Fermont, 562 km of mostly unpaved driving, there are two gas stations. You’ll use at least one of them.

Located about 8km from the border and 23km from Labrador City, Fermont’s roughly 2,800 residents make their living in the iron mining industry. It’s sole purpose is to house the workers at nearby Mont Wright (“Iron Mountain”) Mine, which started operations in the early 1970s.

The town, which is the northernmost francophone settlement of any real population, was modelled after a northern copper mining settlement in Sweden.

The word ‘town’ is misleading, as the inhabitants of Fermont and all of its shops, institutions and amenities are contained within a single, massive building. 1.3 kilometres in length and 160 feet high, the building allows occupants to travel to the bank, the hockey arena, and the liquor store without ever having to go outside.

A number of smaller buildings exist on the leeward side of the building, which serves as a windbreak in the winter. Fermont’s record low temperature is minus 49.5 degrees Celsius (not counting windchill), meaning that being inside the big building is best.

The Quebec mining town of Fermont was built in the early ’70s to supply a new iron mine to the west. The town is essentially a massive building that houses all apartments and amenities, measuring 4,300 feet long.

For that alone, the place is creepy. I ventured inside for a bit, stopping at the local bar where I polished off a Molson Dry amongst the mainly silent patrons.

For two small settlements hundreds of kilometres from the nearest town, Fermont and Labrador City-Wabush are a study in contrasts. Fermont is almost exclusively francophone, while Labrador City-Wabush is primarily English-speaking. Despite being separated by less than half an hour of driving, Fermont recognizes Eastern Standard Time, while all of Labrador uses Atlantic Time.

And, when the booze stores close up in Labrador, they’re still open in Quebec, meaning that stretch of highway gets a workout.

Speaking of which, after the rally race that was the previous several hours of driving, gliding along that freshly-paved highway Between Fermont and Labrador City was luxurious. I felt like Elaine in Seinfeld, stretching my neck and marvelling over the “extra-wide lanes.”

Crossing the border was a celebratory event, marked by a photo and a bathroom break. Even more exciting was entering Labrador City (population 9,354), where I bowed down at the base of a street light and saluted a Tim Hortons. It was good to be in a pocket of civilization.

With the exception of the Newfoundland ferry terminal in Blanc-Sablon, Quebec, this is the only way to leave (or enter) the Big Land by car.

Labrador City has the distinction of having the only indoor shopping mall in Labrador (fun fact!), so I made a point of visiting. Yes, the Labrador Mall (what else would it be called?) was hopping that day, as was the Wal-Mart.

Before finding a room and grub I briefly visited the offices of The Aurora, a weekly newspaper serving the Labrador West area.

When I judged a feature category of the Canadian Community Newspaper Association awards in 2008, the winning article came from The Aurora. It was a well-deserved win, though at the time I had no idea I’d find myself in their neck of the woods a year later.

Given the distance I’d travelled that day, leaving Labrador City to drive the five kilometres to Wabush (population 1,861) was a little anti-climactic, despite me having reached my goal.

In addition to the luxury of a warm hotel room, I celebrated by indulging in the weekly Chinese buffet (very popular, I was told) they held in the downstairs restaurant. Hungry as hell, I was halfway through my plate before I realized it was the worst Chinese food I have ever eaten.

“Oh, you’ve been up The Road,” said a gas station attendant upon seeing my car.

I’m no foodie snob. I like my meals like I like my gasoline – cheap, and plentiful – but this had the feel and texture of a cook approximating Chinese food, having never encountered the real thing before.

Now that I was in fabled village of Waknuk, I wandered next door to a community centre to talk to some folks about the literary significance of their remote town. No one at both the centre or the hotel knew of the connection, nor did the reporters at the newspaper.

It is, at the end of the day, just one novel. I shouldn’t have been surprised.

In conversation with a mother and son who worked at the community centre, I was told of how Labrador exists off the radar of most Canadians, and how this is the perception of most Labradorians.

“People don’t have much of a sense of what Labrador is,” I was told by the friendly family, and I couldn’t have agreed more.

I have more of a sense now, after having visited twice, albeit briefly. A new life goal is to drive the entire Trans-Labrador Highway, from the border with Quebec in the west, to the border with Quebec in the south. Bridging the two areas I’ve seen, while filling in all the rest.

I left Wabush the next day, heading home. Stopping for coffee, I was told by an employee of Tim Hortons that they brew their coffee stronger “than on the outside,” an interesting use of terminology.

At the gas pump (full service!), the attendant looked at my mud-and-grit-plastered Grand Am with an expression of surprise.

“You’ve been up the road!” he said, before noticing the out-of-province plates.

“Yes, and I’m headed back down now,” I replied.

He looked me in the eyes and said, almost like a pastor, “Have a safe journey.”

****************************

The road back (as you can imagine) was more of the same, but my rally instincts were honed again just south of Manic-5 when those same Hydro-Quebec crew cabs decided to tailgate me on their 214km trek back to Baie-Comeau.

Maybe my Ontario plates made me a thing to be toyed with. Regardless, this lone individual in his old Grand Am gave those seasoned back-roaders a run for their money. We all made record time back to town.

The Quebec-Labrador border (in distance, at curve) appears after 570 km of Route 389. This is Labrador’s only overland road link to the rest of Canada.