The Silver Hawk (1957-59) replaced the Flight Hawk and Power Hawk in the Studebaker line. (Spotted in Arnprior, Ontario)

It’s one of those cars that makes you wish you were living in the ’50s.

The part after the polio vaccine.

Anyone wandering by this stunning 1959 Studebaker Silver Hawk would assume its vibrant, triple-tone paint job, plentiful chrome and unapologetic tail fins were the product of a company awash in money and idealism.

Not true.

The 1959 Silver Hawk escaped the cost-cutting being performed by a financially desperate Studebaker.

The car this Silver Hawk was based on – the radical 1953 Studebaker Starlight, sculpted by legendary designer Raymond Loewy – did emerge in a time of seemingly limitless postwar bliss – for both America and Studebaker.

Six years later, Studebaker’s fortunes had fallen drastically, and the Indiana-based company was in what Lee Iacocca would call ‘triage mode’. An ill-fated merger with Packard and a myriad of other issues saw Studebaker in the red, leaking money, and struggling to survive.

The Loewy-designed coupes – Starlight (pillared coupe) and Starliner (pillarless hardtop) – were given a re-working for 1956 to freshen their appearance, and were expanded into five models. The Flight Hawk, Power Hawk, Sky Hawk, Silver Hawk and top-line Golden Hawk oozed ‘1950s’, but didn’t sell in enough numbers to balance the company’s books.

Powered by a 259 c.i.d. V-8, the 1959 Silver Hawk served as Studebaker’s flagship during that lean year.

In the background of these glorious models, the parent company was doing everything possible to cut waste and increase revenues, with moderate (but ultimately limited) success. The stodgy Studebaker Champion was stripped down to become the entry-level Scotsman (1957-58) and the same car was chopped and shortened to become the spacious ‘compact’ Lark (1959-64).

Those models gave Studebaker just enough money to struggle onward rather than folding altogether. In the waste-cutting department, the Silver Hawk – Studebaker’s best-selling Hawk model – was kept for 1959 while the others were canned.

The ’59 Silver Hawk was available with a 170 c.i.d. inline-six making 90 horsepower, or a 259 c.i.d. V-8 making 180 or 195 horsepower, depending on carburation. Buoyed by the success of the Lark, Studebaker saw renewed interested in the Silver Hawk that year, selling 7,788 units.

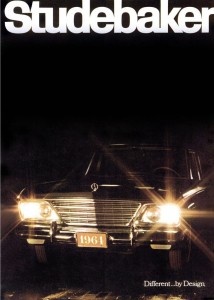

The Silver Hawk name was abbreviated to just ‘Hawk’ for 1960 and ’61, as Studebaker soldiered on into a decade it wouldn’t survive. The body remained exactly the same for those model years, though an upgrade engine appeared in the form of the company’s 289 c.i.d. V-8 (making 210 to 225 horsepower).

A transmission upgrade was also offered in 1961.

The last of the Hawk lineage – the 1962-64 Gran Turismo Hawk – is still a classic, despite being a facelifted model based on 11-year-old architecture. Right up until its demise in 1964 (1966 in Canada), Studebaker had the uncanny ability to transform dated designs into something reflecting its era.

Call it ‘grace under pressure.’